Some 70 years ago in Singapore, a breed of woman arose that took the future of all Singaporean females into their hands. This International Women’s Day, Mummyfique celebrates the foremothers that gave birth to women’s rights in Singapore.

Social Change for Wives and Mothers in Singapore

Imagine being married off to a man without any certification. Instead, your parents and his parents agree you would make a suitable heir-producing bride for their son, and it’s a done deal. Imagine, a few years down the road, after you’ve had your third, maybe fourth child, you stop expecting your husband home nightly, or weekly, or monthly. Hence, you make do with whatever little money he sends or find jewellery to pawn off to feed the family. One day, he finally comes home, and you get into a fight. He beats you up and tells you he now has a second wife and family. Now, you’re left on your own, trying your best to eke a living doing whatever work you can get, anything to keep your children alive.

Such a scenario would be unfathomable for most Singapore women today. But for many of our great-grandmothers or grandmothers, this was too common a scenario during their day. Up to the 50s and 60s, women in Singapore had few rights. Marriage was agreed upon without legal documentation. Children were born, and not all had birth certificates, and some were sold off. Men could have as many wives as they liked—the more honorable among them would ensure that each wife was properly looked after, with a roof over her head, and money to run each household. More often though, husbands simply disappeared and went off to start new families as they liked.

The fate of women in Singapore might have remained unchanged if not for a handful of women who saw that it was up to them to fight for change. Here are three pioneering female social activists—among a host of many more—who changed life for women in Singapore for good.

SHIRIN FOZDAR

Her Early Years

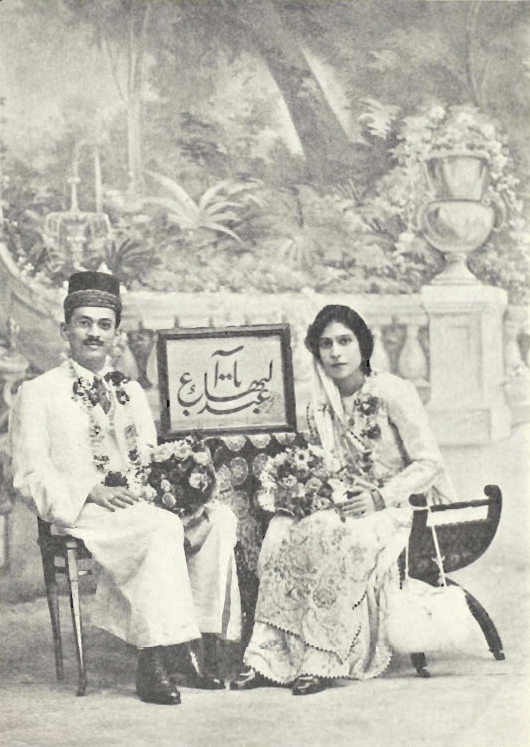

A name well-associated with the birth of women’s rights in Singapore, Shirin Fozdar, who was born in Bombay, India to Persian parents, came to Singapore in 1950 with her husband Khodadad Fozdar, a medical doctor, to spread the Bahá’í faith. Since her teens, Shirin was a trailblazing women’s advocate speaking out about education for women and issues such as polygamy and child marriage. By the time she arrived in Singapore she was a renowned public speaker throughout Asia.

The Fight for Women's Rights

What she encountered was the shocking reality of polygamy—wealthy men showing off their latest in a string of wives at social events—and divorce—60 per cent of Malay marriages ended in divorce since men could end their marriages without warning. The fact there was no legal protection for women or girls at all drove Shirin to action.

In November 1951, she gathered a group of like-minded women at her home to discuss how to help women in Singapore attain rights, and this became the seeding ground for Singapore Council of Women (SCW) which was formally established in 1952. Shirin was the elected honorary general secretary, handling communications with the media and politicians. SCW was Singapore’s first political action organization formed by and run by women and boasted 800 members within a few months, growing to 2,000 members, making it the largest women’s organization for 50 years.

Establishing the Syariah Court

Shirin fought for many things, but her biggest bugbear was marriage inequality. At that time, the law gave husbands great power to divorce and remarry at will, while their wives had no legal recourse. Together with her compatriots at SCW, she campaigned relentlessly to change this state of things for women.

Breakthrough came in the form of the establishment of the Syariah Court in 1958. Shirin had been corresponding with the then-Chief Minister David Marshall about the plight of Muslim women stranded by easy divorces granted to Muslim husbands. The new court, which had jurisdiction over marriage and divorce, could order husbands to pay alimony. Such procedures resulted in a sharp decline in the number of divorces in the Muslim community.

Outlawing Polygamy and Championing Girls’ Education

Perhaps Shirin’s greatest contribution was the impact of her active lobbying for polygamy to be outlawed. She continually wrote to government officials, community leaders and the media to push for monogamous marriage law, and her efforts paid off when the People’s Action Party made women’s rights a key agenda in their election campaign. The PAP won the election, and the Women’s Charter was passed in the Legislative Assembly in 1961. With the Charter, polygamy became illegal for non-Muslims and women in Singapore finally won fundamental rights.

Shirin moved to Thailand in 1958 after her husband passed away. There she served destitute women and girls by setting up a school to offer at-risk girls education. In 1975 she returned to Singapore and continued to be a writer and an advocate of the Baha’i faith.

She passed away in 1992 from cancer, at the age of 87.

TAN CHENG HIONG

Galvanised into Advocating for Women’s Rights

Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned. Tan Cheng Hiong channelled the negative energy brought about by her husband’s infidelity into powerful advocacy for women’s rights, chiefly the banning of polygamy in Singapore.

Better known as Mrs George Lee after she married the brother of philanthropist Lee Kong Chian, Cheng Hiong was a contented wife and mother of nine, despite having a condition that made each pregnancy difficult and painful. That was, until her husband decided to have a second wife.

According to the Singapore Women’s Hall of Fame, she said, “After 15 years of marriage and nine children, my world came apart when my husband took a concubine. At one point, I even contemplated suicide.”

Instead of allowing herself to be overwhelmed by self-pity, Cheng Hiong chased her husband out of their home, and focused her attention on helping other women. Although she appeared to be every bit the traditional Chinese wife on the surface, since she was a young girl, Cheng Hiong had a passion for alleviating the pain women suffered. Both her grandmother and mother had observed the custom of binding feet, a tradition Cheng Hiong considered barbaric. When she saw women with bound feet working in her husband’s family factory, she convinced him to install pulleys in the factory so that the women did not have to hobble up and down the stairs carrying heavy sheets of rubber.

Forming the Singapore Council of Women

Serendipitously, she met Shirin Fozdar in 1952 when Shirin was gathering like-minded women to form the SCW. Cheng Hiong became the first president of the SCW, with Shirin serving as general secretary. That same year she and SCW lobbied factories to set up childcare facilities for the working mothers—an idea vastly ahead of its time. In 1953, SCW set up a girls’ club at Joo Chiat, which Cheng Hiong funded, and also contributed her time teaching sewing and Mandarin.

Abolishing Polygamy and Making Monogamy Legislation

Although they could not be more different, Cheng Hiong and Shirin formed a powerful duo. Shirin was the outspoken one who handled communications, Cheng Hiong—dubbed “the quiet crusader of the women’s movement in Singapore”—moved the chess pieces behind the scenes that would lead to change.

One such move was a letter she penned to the Chinese Advisory Board which the Governor depended on for wisdom on important matters. Her letter detailed how concubines and mistresses were unjustly treated according to Chinese custom, how polygamy was an outdated and cruel practice that hurt women and children, an abomination that had no place in the modern colony known as Singapore.

In her quiet way, she rallied support from law makers and groups to ban polygamy, and she succeeded: in 1961, when the Women’s Charter Bill became law, monogamy became legislation.

Cheng Hiong served as president of SCW until 1959, then vice president until 1971 when SCW was deregistered. She passed away in 1999 at the age of 95.

CHE ZAHARA

Her Early Years

If she was alive today, Che Zahara binte Noor Mohamed would probably still be tearing down any remaining walls of social injustice. With the support of the men in her life, she rose to become one of Singapore’s most prominent pioneering activists.

She was born into an illustrious family in Singapore in 1907. Her father Noor Mohamed was an important figure and one of first Malays to learn English and work as a mediator and translator during British rule; it was he who taught his daughter to speak English.

Caring for Women and Orphans

Che Zahara married a Ceylonese businessman, Alal Mohamed Russull, who was a strong advocate of social welfare. He encouraged his wife to follow her heart to bring change to poor women and children.

After World War II, many women were widowed, and many had no option but to turn to prostitution to earn money to survive. Hence, Che Zahara and her husband began taking orphans and vulnerable women into their own home on Desker Road. Over the course of more than a decade, she looked after over 300 women and orphans of all races and religions. Those she took in also had the benefit of learning skills such as sewing. In the beginning, she paid for this effort. However, she soon realised she could not continue doing so with the numbers of the needy growing. Hence, she created a booklet to appeal for donations worldwide, and succeeded in raising $500,000—a sum unheard of in the day.

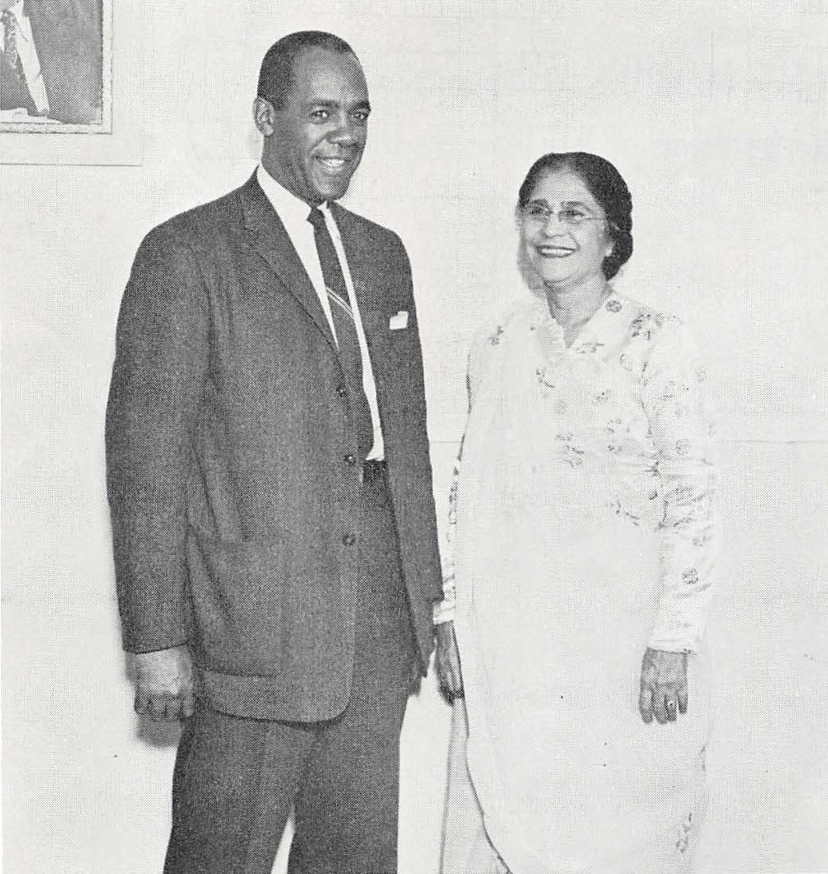

She was selected as representative of Singapore at the World Congress of Mothers in Lausanne, Switzerland in 1955. This was an opportunity Che Zahara took full advantage of, using the platform to gain international support for her work in Singapore.

Advocating for Muslim Women

Che Zahara was a woman of many achievements, but chief among them was her founding the Malay Women’s Welfare Association (MWWA) in 1947, the first Muslim women’s welfare organization in Singapore. Through MWWA she lobbied for major changes to the rights accorded Muslim women.

Her advocacy took all sorts of forms, including the creative. In 1948, she wrote four plays that spoke out against traditional Malay marriage customs, including the ability of a man to divorce his wife without going through legal procedure. She also fought for husbands to support their wives financially for life, or in cases of divorce, until their former wives remarried. In addition, she supported the Laycock Marriage Bill, which made it illegal for girls under 16 to be married—before this, girls as young as nine could be married off.

Truly a trailblazer, Che Zahara and MWWA planned the first public procession by women seeking to celebrate the 1947 Royal Wedding of Princess Elizabeth, the future Queen of England. Although the march did not happen, she had succeeded in bringing about debate about the place and rights of women.

It has been said that the existence of MWWA spurred the establishment of the SCW. Che Zahara was one of the like-minded women that Shirin Fozdar roped into forming the SCW—she worked with the organisation to establish the Women’s Charter of 1961. When MWWA dissolved, she joined the SCW.

Che Zahara was a woman far, far ahead of her time, a thinker who thought beyond the span of her own life. She gave her all to fighting for a better, safer world for those who did not have a voice of their own. She died in 1962.

Sources:

Shirin Fozdar

Lam, J. L. (Ed.). (1993). Voices & choices: The women’s movement in Singapore. Singapore: Singapore Council of Women’s Organisation and Singapore Baha’i Women’s Committee, pp. 90–97, 146-147. (Call no.: RSING 305.42095957 VOI);

Chew, P. G. L. (1996). The emergence of the Baha’i faith in Singapore (1950–1972). The Singapore Bahai Studies Review, 1(1), 30–32. (Call no.: RSING 297.9305 SBS)

Chen, A. (1990, August 9). One man, one wife – and one grand old dame. The Straits Times, p. 78. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chew, Phyllis Ghim Lian (March 1994). “The Singapore Council of Women and the Women’s Movement”. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 25 (1): 112-140. doi:10.1017/s0022463400006706. hdl:10497/4646

Ways to reduce polygamous marriages. (1959, August 13). The Singapore Free Press, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG;

Pioneer of women’s rights dies. (1992, February, 6). The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Roots.sg. (2019).

Shirin Fozdar. Retrieved 2020, March 5 from National Heritage Board website: https://www.roots.sg/learn/stories/shirin-fozdar/story

Ong, R. (2000). Shirin Fozdar: Asia’s foremost feminist. Singapore: The author, pp. 45, 48-49. (Call no.: RSING 297.93092 ONG);

Shirin Fozdar Trust Fund. (1993, July/December). High Networth, 17(13), 76. (Call no.: RSING q332.605 HN)

Che Zahara

Latiff, Sham (1 January 2015). “Che Zahara, Silent Heroine of Singapore”. Aquila Style. Archived from the original on 4 January 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

LI, MUHAMMAD AIDIL BIN (2012-04-19). SAVING THE FAMILY: CHANGING ATTITUDES TOWARDS MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE IN THE MUSLIM COMMUNITY IN THE 1950s AND 1960s (Thesis thesis)

Protest On Malay Marriage Customs”. The Straits Times. 9 June 1948. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

Hughes, Tom Eames (1980). Tangled Worlds: The Story of Maria Hertogh. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 42. ISBN 9789971902124.